Please enjoy this guest post by two writers who’ve addressed the issue of mother-daughter caregiving through fiction and memoir: Diana Y. Paul, Ph.D. and Virginia A. Simpson, Ph.D

Parents are expected to take care of their children, but they usually do not anticipate a future where their children will take care of them. Nor are adult children prepared to take care of their parents. Due to the record longevity of our parents, more and more of us are expected to participate in caregiving. So, anticipate a longer-term, intimate relationship between adult child and aging parent.

We all need to prepare for this eventuality. After years of managing for themselves, parents usually and naturally do not welcome being told what to do. Most of us are—or will face—this role-reversal, and we can’t do it alone.

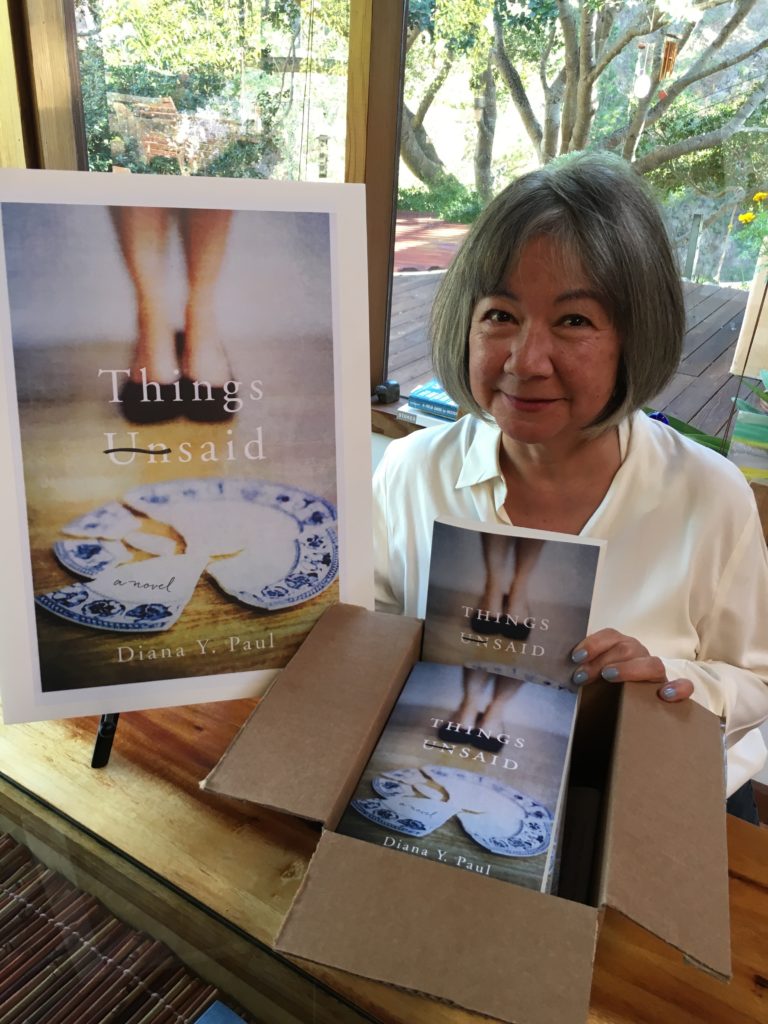

Fictional Caregiving In Things Unsaid

The challenges of being stuck in the middle and taking care of two families—the so-called “sandwich generation”—are immense and often debilitating. Partly because the family dynamics of one’s youth influences caregiving, caring for one’s parents is much more difficult than caring for one’s kids. Financial and emotional stressors also arise, intensifying the inherent conflict and difficulty of caring both for oneself and for one’s parents.

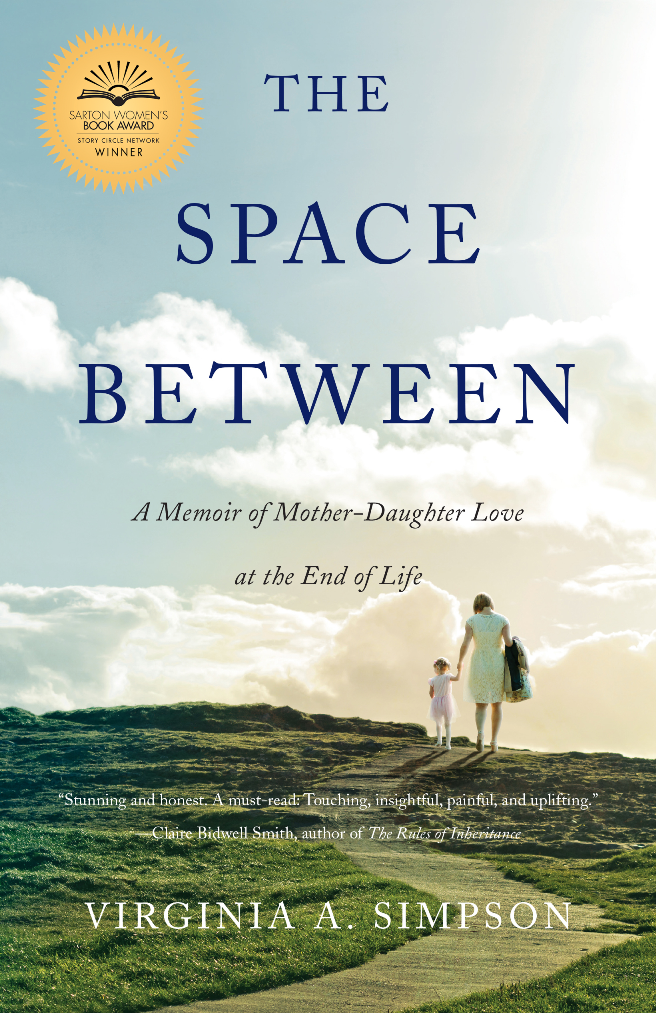

The theme in our two authorial debuts Things Unsaid (a novel) and The Space Between: A Memoir of Mother-Daughter Love at the End of Life (a memoir) touches upon the all-too-typical dysfunctional family, its dynamics, and what happens in the end: the last chance to make things right. Both books are portraits of the way unresolved issues from childhood and ongoing conflicts complicate the mother-daughter relationship when the daughter becomes the caretaker. Even today, because of tradition, daughters are the ones primarily relegated to the caregiving responsibilities for their parents.

For those with less than loving parent-child relationships, the caregiver’s tasks which require relatively little direct contact with a parent also involve minimal emotional exchange, friction or disappointment.

Assistance with shopping, housework, medication management, and living arrangements are described in Things Unsaid, but the attachment bond between daughter and mother is fragile. Old memories continue, for the most part, beneath the surface. The main character, Jules Foster, is responsible yet emotionally safe. “That’s what a good daughter is supposed to do–love her mother even if her mother doesn’t love her back.” (Things Unsaid)

A Caregiving Memoir: Daughters Caring for Mothers

In The Space Between the author is the caregiver: “…as a daughter, I would never abandon my mother, no matter what.” And the book’s narrator is diligent in her practical eldercare for a mother who is often unaware of the attention and emotional costs on her daughter. In both books, we see forms of unconscious, psychological damage inflicted by mothers on their underappreciated daughters.

Daughters may be less motivated to invest emotional energy in a relationship that has been unsupportive or painful and whose end may be unremarkable or even a relief. Or, daughters may see this as their last opportunity to heal the relationship.

However, when the power-dynamics shift, long forgotten grievances can play out. In Things Unsaid, we see secrets, lies, and betrayal, most notably, on the part of the aging mother. In The Space Between, we see a nonfictional equivalent—including an almost identical scene when a ring promised to one child is bestowed on another.

Sibling Rivalry

In Things Unsaid, we see how three adult siblings disagree about what to do with their parents. At the same time, the parents are manipulative, pitting one sibling against the others. In The Space Between we see the favoritism towards the half-brother and how the caregiver suffers.

So what is the well-meaning daughter to do? The daughter’s need for her mother’s love and attention isn’t diminished by the mother’s abandonment or dismissal. In Things Unsaid we see little emotional connection overall, and in The Space Between we see a strong, but not always healthy, emotional connection.

Yet in both stories there is a fierce sense of obligation. In Things Unsaid, even at the end, this is never enough nor is it satisfying, while in The Space Between, the daughter finds the reconciliation and love she’d been hoping for her whole life.

The Possibility of Healing

In both books we see the possibility of healing at the end of the mother’s life. Although not always redemptive or forgiving, there is a moving forward towards the future, made possible by the daughter’s letting go of the past. The grown child and her mother have severed the unhealthy dynamic of an earlier time.

While neither of us is advocating any a particular philosophy of caregiving, we feel family education programs that examine interpersonal dynamics before caregiving becomes a necessity could hold the key. These programs offer families an opportunity to discuss caregiving expectations and address discrepancies across generations before they evolve into conflict and regret.

Research that explores connections between emotional and behavioral family patterns will be vital for understanding the difficulties of eldercare.

The stories and themes addressed in The Space Between and Things Unsaid are in all of us. By showing the challenges and victories with brutal honesty, both of our books shine an important light on how we can meet the challenges of role reversal with our sanity and spirit intact.

Authors’ bios:

Diana Y. Paul has a degree in both psychology and philosophy from Northwestern University and a Ph.D in Buddhist Studies from the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Her debut novel, Things Unsaid, won the Beverly Hills Book Award 2016 for New Adult Fiction, the Readers Favorite 2016 Silver Award for Best Fiction, was nominated for a Pushcart Prize, and listed as #2 on Brit.co’s “14 Books about Families Crazier than Yours”. A former Stanford professor, she is the author of three books on Buddhism. She lives in Carmel, CA with her husband and calico cat, Mao. Diana is currently working on a second novel, A Perfect Match, and when not writing, creates mixed media art. Visit her author website at: http://www.dianaypaul.com

Virginia A. Simpson, Ph.D., FT is a Bereavement Care Specialist and Executive Counseling Director for hundreds of funeral homes throughout the United States and Canada. She is the Founder of The Mourning Star Center for grieving children and their families, which she ran from 1995 to 2005, and author of the award-winning memoir The Space Between (She Writes Press, April 2016) about her journey caring for her ailing mother. She holds a Fellowship in Thanatology from the Association for Death Education & Counseling (ADEC) and has been honored for her work by the cities of Indian Wells, Palm Desert, Palm Springs, and Rancho Mirages. Visit her author website at: www.virginiaasimpson.com